Missourians harvest the food we eat, build local homes and businesses, keep our communities safe, and teach our children. They are the engines of our economy, supplying the products and services we use every day. Those same Missourians are consumers, providing customers to businesses in our state when they spend money.

Although workers’ median wages have slightly increased, recent inflation has diminished much of those gains. Workers earning the state’s minimum wage are especially impacted by rising costs and are paid far less than what families need to afford basic necessities and maintain a decent standard of living. In fact, more Missourians are finding it harder to get by today than they did when the economy was recovering from the pandemic.

In November, Missourians will have the opportunity to vote on Proposition A, which would ensure workers have access to paid sick leave and increase the minimum wage so Missourians can care for their families. With these economic safeguards, workers can contribute more fully to their jobs and communities, as well as the broader economy. By enacting Proposition A, Missourians can strengthen communities and build an economy that works for everyone.

Missouri Workers’ Earnings Stagnant in Last Twenty Years

A Missourian who earns the state’s minimum wage of $12.30 an hour and works full time earns just $492 per week, leaving many of them unable to afford basic necessities.

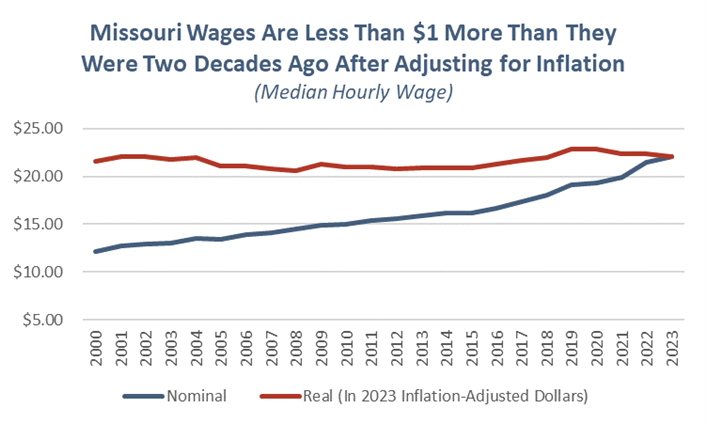

Even workers with higher incomes are struggling to keep up with costs. Although the median wage in Missouri has nominally increased, the real value of those wages has been nearly stagnant since the turn of the century.

In 2000, a worker earning the median wage made $12.12 an hour – the equivalent of $21.57 after adjusting for inflation (in 2023 dollars).

Earnings have barely budged since then. In 2023, a worker earning the median wage made just $22.09 an hour, meaning half of Missouri workers earned more, and half earned less.

Inflationary Increases Have Made It Even Harder to Keep Up

Workers’ economic struggles were compounded by fast rising prices that were triggered by COVID-19 pandemic supply chain issues and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and then largely fueled by excessive corporate profits. Although inflation slowed in 2023, it is still a problem for many workers. Inflation grew 3.8% in 2023, while the nominal median wage grew at a slower pace of 2.7%. The higher cost of basic necessities like food, housing, gas, and utilities continues to strain the budgets of households living paycheck to paycheck.

As of May 2024, nearly 40% of adults in Missouri live in households that had difficulty paying for usual household expenses, up from nearly 25% in 2021.

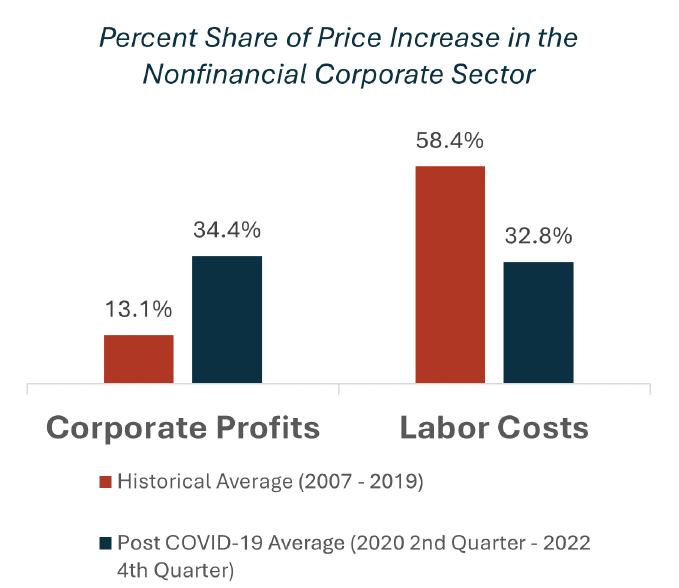

Corporate Profits Contributed Disproportionately to Price Growth in the COVID-19 Economic Recovery

Corporate profits are a primary driver of the recent wave of inflation. From 2020 through 2021, nearly 54% of the increase in an item’s price can be attributed to corporate profit, followed by non-labor costs (38%), and the cost of labor (8%). Although the corporate profit share declined to 34% by the end of 2022, it was still well above the historical average of 13%.

To the contrary, the share of an item’s price attributed to labor costs was well below historical trends.

Low Paid Workers Have Fewer Opportunities to Get Ahead

More than 1 of every 6 workers in Missouri made less than $15 an hour in 2023. This is more than a third less than what a family of four with two working parents needs to cover basic living expenses, according to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Living Wage Calculator for Missouri.

Workers earning low wages are far more likely to have unstable jobs with unpredictable schedules and involuntary part-time work, compared to higher wage earners. This financial instability and insecurity makes it difficult for these workers to meet the basic needs of their households:

- In 2022, nearly 80% of Missouri families receiving public food assistance from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) included someone who worked in the past twelve months.

- An estimated 1 in every 15 workers relied on Medicaid public health insurance for individuals with low incomes.

Notably, critical workers who were deemed essential during the COVID-19 pandemic – food service workers, childcare workers, and home health aides – are still among the state’s lowest paid workers.

| Major Occupation Category | 1 of every 4 workers are paid this wage or less |

|---|---|

| Food Preparation and Serving Related | $13.20 |

| Personal Care and Service | $13.07 |

| Healthcare Support | $13.33 |

Low paying jobs also tend to offer fewer benefits. An estimated 1 in every 9 Missouri workers lack health insurance, and 1 in every 3 workers do not have access to paid sick leave. These workers must often choose between going to work sick, which threatens the health of their coworkers and customers, or risk losing a day’s pay.

Missouri’s low-paid workforce mirrors that of the rest of the country, in that it is disproportionately women and people of color. The state’s long history of racial/ethnic and gender discrimination and occupational segregation excluded many of these workers from opportunities that would have increased their earnings and subsequent wealth. Still today, their work is undervalued, they are discriminated against in the job market, and they often encounter multiple barriers and fewer job opportunities. All are factors that leave them vulnerable to jobs that lack worker protections and adequate compensation.

Characteristics of Missouri households with low income:

- Among full-time, year-round workers in 2022, 13.5% of women earned less than $25,000 a year, compared to just 8.7% of men.

- In 2022, an estimated 20.4% of Black families and 14.7% of Hispanic and Latino families had annual incomes below $25,000, compared to just 8.0% of non-Hispanic white families.

- A disproportionate number of low-income households with children are headed by women. In 2022, an estimated 12% of families with children under age 18 had annual incomes below $25,000. About 2 of every 3 of those households are headed by females with no spouse present.

Conclusion

When employers treat workers fairly—by paying thriving wages, providing stable and predictable work hours, and offering paid time off so workers can address theirs or their families’ health needs without losing their jobs or the ability to pay their bills—workers are more able to reach their full potential. This in turn allows workers to contribute more fully to their jobs and communities and the broader economy.